What Are You Buying When You Buy The S&P 500?

Applying our forward returns framework to the stock market by treating it like one company.

Howard Marks’ recent memo, On Bubble Watch, eloquently put into words several of the observations Matt and I traded over the last couple of months.

Marks compares and contrasts the current financial markets to previous periods of euphoria which often preceded a bubble and subsequent collapse. Marks thinks that US stocks today are historically expensive and offer poor, but not catastrophic risk-adjusted prospective returns. This seems about right to me, as I’ll elaborate on in this post.

We are long-term bottom-up investors and usually make it a point not to discuss “the market” and macro on this blog. The macro is already analyzed to death, and we think insights are easier to come by in the micro. We don’t make predictions about where the market will go over short periods of time (anything less than five years).

That said, we do think it can be helpful to understand where stocks in general stand and what their prospective returns might be over the coming decade. One method is to analyze the S&P 500 as if it were a single stock using our typical forward returns methodology. An exercise like this may help investors understand their opportunity cost and balance aggression versus conservatism.

Analyzing The S&P 500 As A Single Company

Our framework for assessing forward returns is based on the sum of the company’s yield (dividends + net buybacks), growth, and change in valuation multiple. These three legs form the basis of our forward returns stool.

Yield

The current dividend yield for the S&P 500 is 1.3%. This is low relative to history because of the index’s high valuation and low payout ratio. Companies are sending a lower percentage of their earnings to investors as dividends compared to history in large part to an increase in share repurchases. The most recent buyback yield I can find, which is a few months stale, is 1.9%. Taken together, the S&P 500’s shareholder yield is 3.2%.

Growth

The S&P 500’s earnings per share has grown 6-7% per year, on average, over long periods of time. Stripping out the per-share impact of buybacks, absolute earnings have grown by 4-5%, or a little ahead of inflation.

Here’s why that’s likely to continue to be the case over the next ten years.

Earnings growth is the product of a company’s reinvestment rate and the incremental return on that retained capital. The S&P 500 currently spends 30% of earnings on dividends and 47% on buybacks, leaving 23% for reinvestment.

The S&P 500’s long-term average return on equity is 14%, according to CSI Market. The exact figure bounces around year to year. A 23% reinvestment rate at a 14% incremental return implies a 3.2% growth rate for the S&P 500.

This estimate may be conservative. Current returns on equity are higher than 14% and companies could use debt to reinvest more than the 23% reinvestment rate implies. Increases in productivity could improve ROE or keep it elevated above its historic average.

On the other hand, corporate profit margins are historically high. Mean-reverting profit margins would likely reduce returns on equity.

On balance, a 4-5% future long-term growth rate seems reasonable and is probably in the right ballpark.

Change in Valuation Multiple

At 22x forward earnings, and around 30x trailing , the S&P 500 is expensive relative to history. This is not an opinion but an empirical fact. Whether it’s expensive relative to what it’s worth is a different question.

One way to value the S&P 500 is to ask: what valuation it would need to trade at to produce 10% forward returns (in-line with its historical average)? If we assume the S&P 500 is going to grow 4-5% then it needs to produce 5-6% of yield to produce a 10% return.

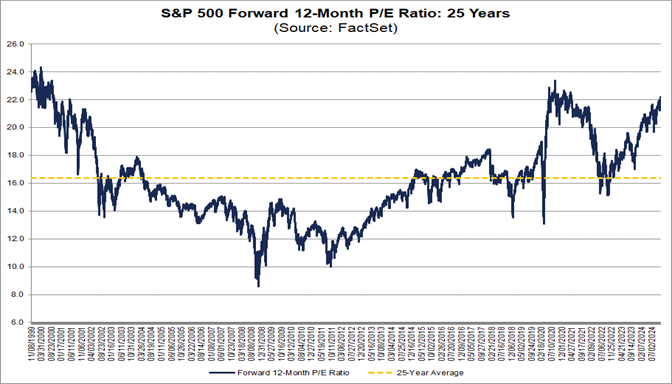

For simplicities sake let’s assume that we can receive roughly the S&P 500’s earnings yield as shareholder yield. (This isn’t quite right, as the S&P retains 23% of earnings. In reality there will be some leverage to help and large companies often generate more in free cash flow than reported earnings, so it’s close enough). This means we need a 5-6% earnings yield to get our 10% returns, which is a 16-20x P/E ratio. Unsurprisingly, the S&P 500’s 25-year average PE ratio is 16x. This compares to the current 22x forward and 30x trailing multiple.

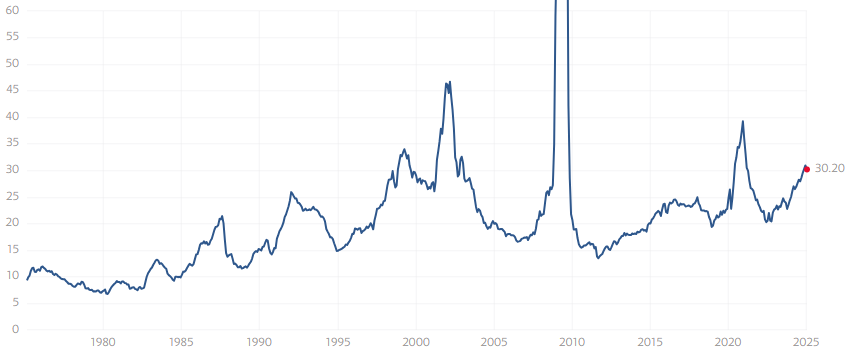

Over the past 50 years, the trailing PE ratio of the S&P 500 has varied dramatically.

Here is what the forward PE multiple has looked like over the past 25 years:

Other than during recessions, when the PE ratio tends to sky-rocket not because of rising stock prices but because reported earnings get wiped out, the stock market has spent plenty of time both well above and well below 20x P/E. As you can see, we’ve spent most of the last 15 years since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008/9 benefitting from a rising P/E ratio. Will that continue? Maybe, but I wouldn’t count on it, for one reason in particular: interest rates.

Interest rates play a big part in valuations because investors tend to demand higher returns, aka a lower starting valuation, from stocks when they can earn higher returns on bonds. The best way to look at this is via the “risk premium” applied to stocks. I wrote more about this a few years ago.

A good proxy for the current risk premium is to look at the earnings yield of the stock market vs. the 10-year yield on U.S. treasuries. The current rate on the 10-yr is about 4.7%. In other words, the 10-yr trades for about 21x “earnings” (1 divided by the interest rate). This also means there really is no equity risk premium for the stock market given the current valuation is above the 10-yr yield. This is another data point suggesting that continued multiple expansion is unlikely. Again, not impossible, but not likely.

The final issue with valuation multiple is it’s the most fickle. It’s tough to rely on the most wobbly leg of the stool of returns to power future returns, especially when that lever has seemingly already been pulled. It could happen, but counting on an expanding multiple to aid returns from here, especially given where present interest rates are, is a real stretch.

So what could returns look like given what we now know about the three legs of the stool?

Forward Returns

We break our forward returns framework into “business returns” and “stock returns.” The business returns equal the sum of yield plus growth, or 7-8%, in-line with history. I’ll use the mid-point of 7.5% for this exercise.

Stock returns add the impact of a change in valuation multiple to the business returns. I like to look at a range of outcomes, so I’ll pick the following scenarios (all over a ten year period):

Scenario #1: there is no change in the stock markets valuation over the next ten years, it starts and ends at 22x forward earnings;

Scenario #2: The stock market reverts to the 25-year average valuation of 16x forward earnings;

Scenario #3: The stock market ends the period at a 25-year low of around 9x forward earnings;

Scenario #4: The stock market ends the period at the 25-year high of 25x forward earnings;

The path to any of these end points could vary dramatically and is almost certainly not going to be smooth, which is why I like to zoom and out think in 10-year increments.

You can plug in your own scenarios for potential PE ratios (and growth for that matter). The important thing is not getting the numbers exactly right, but rather taking time to think about how yield, growth, and valuation impact forward returns.

To me, it seems like a tall ask for the S&P 500 to continue to deliver the mid-teens returns it’s produced over the past 15 years. There’s been a huge tailwind of multiple expansion, having started that 15-year period at 9x forward earnings, their lowest valuation in 25 years. That tailwind is unlikely to repeat.

J.P. Morgan recently released a chart that shows the S&P 500’s historical 10-year rate of return from various forward P/E starting points.

Howard Marks’ cited the chart in his memo, saying:

“The graph, from J.P. Morgan Asset Management, has a square for each month from 1988 through late 2014, meaning there are just short of 324 monthly observations (27 years x 12). Each square shows the forward p/e ratio on the S&P 500 at the time and the annualized return over the subsequent ten years. The graph gives rise to some important observations:

There’s a strong relationship between starting valuations and subsequent annualized ten-year returns. Higher starting valuations consistently lead to lower returns, and vice versa. There are minor variations in the observations, but no serious exceptions.

Today’s p/e ratio is clearly well into the top decile of observations.

In that 27-year period, when people bought the S&P at p/e ratios in line with today’s multiple of 22, they always earned ten-year returns between plus 2% and minus 2%.”

Given the realities of economies and financial markets, hoping for anything more than mid-single-digit returns from the S&P 500 might be setting one’s self up for disappointment. After all, it hasn’t happened before.

One final thought on valuations because it gets so much attention: there is no law of nature that dictates the valuation of the S&P 500 must revert to a historical average – or even be reasonable. There is certainly an argument that given the improved quality of businesses, higher returns on equity, general acceptance from the public that stocks are an attractive asset class, and immense passive flows that help support the stock market during periods of weakness, that the next 25 years will result in a significantly higher average valuation for the stock market than the last 25 years.

Given that, I don’t think a PE of around 20x for the S&P 500, while clearly not cheap, is egregious. But, I also don’t think it leaves a lot of upside for multiple expansion or, especially, room for error.

What can we do about all of this?

Anyone who invests in the stock market cannot change the current starting point. All you can do is play the hand you are dealt and try to make the best decision given your situation and objectives. The options I see for those – of which I believe there are many – that are worried about the current high valuation of the indexes are four-fold.

Option one is to own the index and hope for the best, but prepare for much lower returns than in recent years.

This is undoubtedly what most people will do, and over the very long-term it should continue to work out just fine, even if returns come back down to earth for many years.

Option two is to hold more cash and/or own bonds that might earn 5-7% per year.

This is what Howard Marks has advocated for recently given the reduced-risk nature of fixed income. Some classes of fixed income appear to offer comparable and potentially better returns than the likely returns of the S&P 500 over the next decade.

Bond returns are contractual while stock market returns are anything but, and for those that can accept a mid-single-digit return for a portion of their investable assets, this is a fine approach.

I would caution about holding cash that yields little in hopes of deploying it into the stock market at lower prices. I’ve seen this play out many times and I know many folks who have been in cash for years and are still waiting for that pullback. Often when the pullback comes, it becomes hard to deploy the cash because you start waiting for a larger pullback and things seem scary. All of a sudden, you’ve missed it and find yourself waiting for the next pullback, sure you’ll deploy that time! Some people have the right temperament for this approach, but most do not.

Option three is to try to pick individual stocks, or find someone to do so on your behalf, that you think will deliver returns in excess of the middling, or poor, prospective returns of stocks and bonds in general, and with less risk of a poor outcome.

Obviously, this is what we have chosen to do, and we think buying simple, predictable, profitable and high quality businesses for low valuations works over long time periods regardless of the macro stock market environment. We believe this will continue to be true for us but only time will tell.

Option four is to look farther afield for more compelling prospective returns. Foreign stock markets, small caps, alternative asset classes like real estate, private equity, or private credit are all areas that may offer superior risk-adjusted returns compared to broad U.S. large caps.

These alternatives can be loaded with excess risk, so buyer beware. We do some of this as well and when done thoughtfully it can be a logical addition to a core investment approach.

In reality, the right answer for most people is a mix of some or all of the above, and that mix just depends on the individual and what their goals and emotional makeup look like.

Summary

The point of this discussion is not to make a prediction, offer doom and gloom forecasts, or even make a recommendation as to what to do. My goal is to help offer a perspective on how to think about the stock market and how to frame potential outcomes over the next decade. The stock market is not some mysterious black box, it’s just a collection of operating businesses, and should be treated as such.

The question investors should ask themselves is: if the S&P 500 was a single company, would I find it an attractive place to deploy capital? If so, how much of my capital?

Does a “company” that earns a 14% return on equity, pays out most of its earnings, could reasonably grow in the mid-single-digits, and is priced at 22x forward earnings offer a compelling or risky investment? I’d guess the answer is somewhere in between. To me, it’s not an obviously good investment, contains more risk and downside asymmetry than most times in recent memory, but also is unlikely, though not impossible, to be a train wreck over the next decade.

We prefer to look for understandable businesses that earn more than 14% on equity, offer similar but more durable growth prospects, earn a good base return through yield, and are priced at half of the valuation of the market or less. So, that’s just what we’ll continue to do. We’ll write some more about businesses that meet these criteria in the weeks to come.

Above all, I’d recommend people carefully assess what they are buying, what their alternatives might be, and more than anything, temper their expectations for the next 15 years compared to the last 15 years.

Do you have a “stranded” 401k from a past job that is neglected and unmanaged? These accounts are often an excellent fit for Eagle Point Capital’s long-term investment approach. Eagle Point manages separately manage accounts for retail investors. If you would like to invest with Eagle Point Capital or connect with us, please email info@eaglepointcap.com.

Disclosure: The author, Eagle Point Capital, or their affiliates may own the securities discussed. This blog is for informational purposes only. Nothing should be construed as investment advice. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further details.

I fully agree... We seem to be pondering the same issues. I recently asked 'is the stock market broken': https://rockandturner.substack.com/p/is-the-stock-market-broken