“I’d much rather own a local rock pit than own Twentieth Century- Fox, because a movie company competes with other movie companies, and the rock pit has a niche. Twentieth Century-Fox understood that when it bought up Pebble Beach, and the rock pit with it.”

— Peter Lynch

At EPC we love to study simple businesses that we can easily understand, and rock pits are about as simple as they come. So as to not offend anyone in the industry, I’ll use the fancy industry term – aggregates – from here on.

Aggregates suppliers mine and crush rocks, which are unsurprisingly an extremely low cost commodity. Gravel costs something like $20 per ton. Normally, commodity suppliers are low-quality businesses locked in perpetual dog fights with competitors with limited differentiation. Yet, aggregates businesses are very high quality, possess pricing power, and have produced excellent returns for investors over long periods of times. Why the paradox?

Overview

The aggregates industry consists primarily of crushed stone, sand, and gravel that are used in a myriad of building applications. The two broad categories of demand come from publicly-funded projects for roads, bridges, water systems, etc. and from private demand in residential and non-residential construction. Non-residential construction demand represents a mix of public and private funding ranging from hospitals and schools to data centers and manufacturing facilities.

Here is a list of end uses from Vulcan’s most recent 10K.

The industry is certainly cyclical, though the businesses that are more closely tied to public projects enjoy far more predictable demand. Around 35-40% of demand for the large industry players comes from the more stable publicly-funded projects.

Single and multi-family housing is obviously tied directly to housing starts and private spending on new facilities is closely tied to the vagaries of the economy and GDP. That said, the industry has experienced steadily growing demand through cycles.

Aggregates companies are all vertically integrated to varying degrees. For reasons discussed later, the higher the mix towards purely aggregates - which entails owning or leasing mines and quarries to mine and crush stones – the better the business. All of the major companies also own lower quality downstream operations like ready-mix cement plants and asphalt businesses along with other often unrelated building products divisions (like fence installations or paving services). Cement and asphalt operations are logical adjacent offerings because most of their inputs are aggregates and the end markets are largely the same. The downstream segments are subject to far more competition and don’t benefit from the same competitive advantages as the aggregates operations.

Vulcan Materials (VMC) and Martin Marietta Materials (MLM) are by far the largest public companies that are heavily tilted towards pure-play aggregates suppliers. The majority of revenue and the substantial majority of their profits are generated via the aggregates segments.

Let’s look at why the aggregates side of these businesses is so intriguing.

Competitive Position

The aggregates industry in general, and Vulcan and Martin Marietta in particular, enjoy a number of formidable competitive advantages.

Local Monopolies

By far the most compelling aspect of the industry is the local monopoly dynamic arising from an exceedingly high weight-to-value ratio. Crushed rocks are dirt cheap, but shipping them is not (because they’re heavy). If a highway project is going on in St. Louis there is no chance an aggregates supplier from Wyoming is going to compete for the job. The cost of freight from far away quarries would cost multiples of the cost of the aggregate itself. In a super-charged variant of Fastenal’s moat derived from the high weight-to-value ratio of supplying screws, this dynamic breeds local monopolies with virtually no competition.

Peter Lynch expanded upon his suggestion that a rock pit is a superior business model compared to a major production studio or jewelry store, and he’s right (as usual).

“I’d much rather own a local rock pit than own Twentieth Century- Fox, because a movie company competes with other movie companies, and the rock pit has a niche. Twentieth Century-Fox understood that when it bought up Pebble Beach, and the rock pit with it. Certainly, owning a rock pit is safer than owning a jewelry business. If you’re in the jewelry business, you’re competing with other jewelers from across town, across the state, and even abroad, since vacationers can buy jewelry anywhere and bring it home. But if you’ve got the only gravel pit in Brooklyn, you’ve got a virtual monopoly, plus the added protection of the unpopularity of rock pits”

As Lynch indicates, not only do rock pit owners benefit from local monopolies, there are also high barriers to entry, one of my favorite moats.

Barriers to Entry

Commodity businesses are typically only intriguing to us when significant barriers to entry exist, and there are plenty in the aggregates industry.

Thanks to stringent zoning and permitting requirements and the desire to not have neighborhoods and metropolitan areas obstructed by big rock quarries, it’s extremely difficult to get permission to dig a rock pit. Restrictions typically curtail expansion in areas where rock pits exist and make adding new ones nearby daunting; both of which serve to reinforce the local monopoly advantage and confer pricing power.

Capital intensity is another, albeit much less significant, barrier to entry. Martin Marietta and Vulcan each have tens of billions of dollars invested in tangible assets and land, and it’s not as if copy cats can spring up in the garage of their parents to challenge the incumbents as is the case with many software businesses. This business takes real capital.

An important result of these barriers to entry (and barriers to expansion) is the significant likelihood that existing reserves become more valuable over time. As supply is constrained due to the aforementioned barriers and demand keeps chugging along (over the course of a cycle or many cycles) then whoever owns the existing supply is going to benefit from some degree of pricing power. The large players have 75+ years of reserves that are bound to only become more valuable over time.

Limited Products Substitution

Counterintuitively, the low cost nature of aggregates is a multi-pronged advantage. We’ve already discussed the high weight-to-value aspect but the lack of substitutability also stems in part from the low cost of the materials.

Currently there are virtually no substitutes for virgin aggregates in the vast majority of applications. In certain cases recycled concrete and asphalt can serve as substitutes but generally these recycled materials do not meet the technical specifications and performance criteria for durability and strength required by builders.

Given the low-cost nature of the product, I find it hard to imagine an even lower cost substitute that also meets the technical requirements is going to burst onto the scene any time soon (or ever). Not a lot of Silicon Valley startups are rushing to invent a new material that costs $20/ton and has to compete with a plethora of local monopolies.

Suffice it to say, aggregates’ position in the construction products industry feels safe for decades to come.

In addition to these attractive industry dynamics, the largest players benefit from scale advantages and irreplaceable assets in strategic locations.

Irreplaceable Assets in Desirable Locations

Given that an aggregates company needs to be close to customers to serve the market, owning quarries in desirable locations is obviously a huge advantage. Both Vulcan and Martin Marietta are well positioned for decades to come given the existing base of reserves. Both businesses have largely bought their way into these markets via a series of bolt-ons and occasional large acquisitions, and the result is that each business has desirable geographic reach next to high-value MSAs.

Here’s an example of what Vulcan’s reach looks like.

Fortunately for someone like me who lacks much original insight, you don’t have to have unique intellect to grasp the desirability of the incumbent’s positions, you just have to read the 10K and Vulcan lays it right out for everyone:

“Over time, we have strategically and systematically built one of the most valuable aggregates franchises in the U.S. with a footprint that is impossible to replicate. Zoning and permitting regulations have made it increasingly difficult to expand existing quarries or to develop new quarries. Such regulations, while curtailing expansion, also increase the value of our reserves that were zoned and permitted decades ago.”

Logistics Network and Operational Excellence

The final benefit unique to Martin Marietta and Vulcan is simply one of scale and operating efficiency. Vulcan was founded over 100 years ago and Martin Marietta more than 60 years ago, and both have spent decades lowering production and transportation costs as well as building their irreplaceable networks.

There are certain markets that are an exception to the local monopoly rule because they just don’t have naturally occurring rock deposits that fit the criteria for the aggregates that need to be used to build roads and buildings. Along the U.S. Gulf Coast and Eastern Seaboard there are limited supplies of high-quality aggregates, so they need to be shipped in. Martin and Vulcan each have access and ownership of cost-effective long-haul transportation such as barges and rail, and can send aggregates from their existing mines that are closest to where the supplies are needed.

Consequently, even where the local monopolies advantage doesn’t exist, the largest players are still able to exploit the logistical hurdle by being among the only ones who can economically transport aggregates to these locations.

Economics

The very best businesses are ones that take almost no capital to run and can enjoy substantial growth while returning all of the profits to shareholders. These businesses are exceedingly rare and aggregates businesses certainly are not in this class. They are, however, quite good businesses.

There is no one “right” way to define a good business. A couple of reliable indicators are a) high returns on tangible capital and tangible equity and b) evidence of pricing power.

Both Vulcan and Martin Marietta earn mid-teens pretax returns on tangible capital (PP&E plus Net working capital) and 30-40% pretax returns on tangible equity thanks to some leverage that the businesses can easily support. These are pretty good figures. The reported GAAP returns on equity are quite a bit lower because of the large amount of goodwill and intangibles sitting on their balance sheets from all the acquisitions over the years.

In my view, when judging whether or not the business is good, the appropriate measure is generally return on tangible equity, and when judging whether or not management is doing a good job deploying capital (or whether it’s a good investment), return on total equity is more appropriate.

Bad businesses can’t consistently raise prices over time, and certainly not in excess of inflation. Vulcan and Martin Marietta can.

Over the last 30 years inflation has run at about 2.7% annually, and Martin Marietta has increased prices at 4.3% annually. This difference may seem trivial, but VERY few businesses can consistently take price in excess of inflation over a 30 year period. Even a percent or so per year of pricing in excess of inflation is massively valuable over long periods of time.

I’m not suggesting these companies’ possess Transdigm-style pricing power, but they can clearly consistently take price. This is not limited to when inflation is benign, either. Last year both businesses hiked prices >10%.

When given enough time, the effect becomes strikingly clear. Since 1998 Vulcan’s gross profit per ton has risen from $2.11 to $5.96.

Here’s the long-term pricing trend going back to the ‘70s for Vulcan. As you can see, pretty consistent price increases despite varying demand, which is a great sign.

You’d expect pricing power and a rock solid (sorry, couldn’t help it) competitive position to result in good investment returns, and recently that’s been the case. Over the last decade both Vulcan and Martin Marietta have returned about 16% annually, or over 340% in total compared to around 12.5% annually, or 230% in total for the S&P 500 (including dividends).

Forward Returns / Valuation

The large aggregates players have grown substantially via acquisitions given the fragmented nature of the industry. There are thousands of smaller rock pit owners across the country and the Vulcan’s of the world are always looking to scoop them up. Despite being the largest players both Vulcan and Martin Marietta have below 10% market share and they estimate there are more than 10,000 aggregates companies in the U.S. alone.

Not surprisingly, this has resulted in highly acquisitive behavior and both businesses have soaked up nearly all the cash they’ve generated in recent years via acquisitions and organic capex. This is both good and bad. It’s nice to have places to redeploy capital as long as the returns are good (and durable). The bad news is local rock pit owners know they own hard to replicate assets and won’t part with their gem of a business for a low price. So, Vulcan and Marietta have to pay up. Despite this, it’s actually worked out pretty well.

Over the past 10 years Vulcan and Martin Marietta have retained 85-100% of the cash the businesses have generated and earned low double-digit incremental returns on this retained capital. This can be a little misleading with serial acquirers because it takes time for the acquired businesses cash flows to show up in reported financials so large acquisitions will appear to depress incremental returns for the first several years but over time the returns get better.

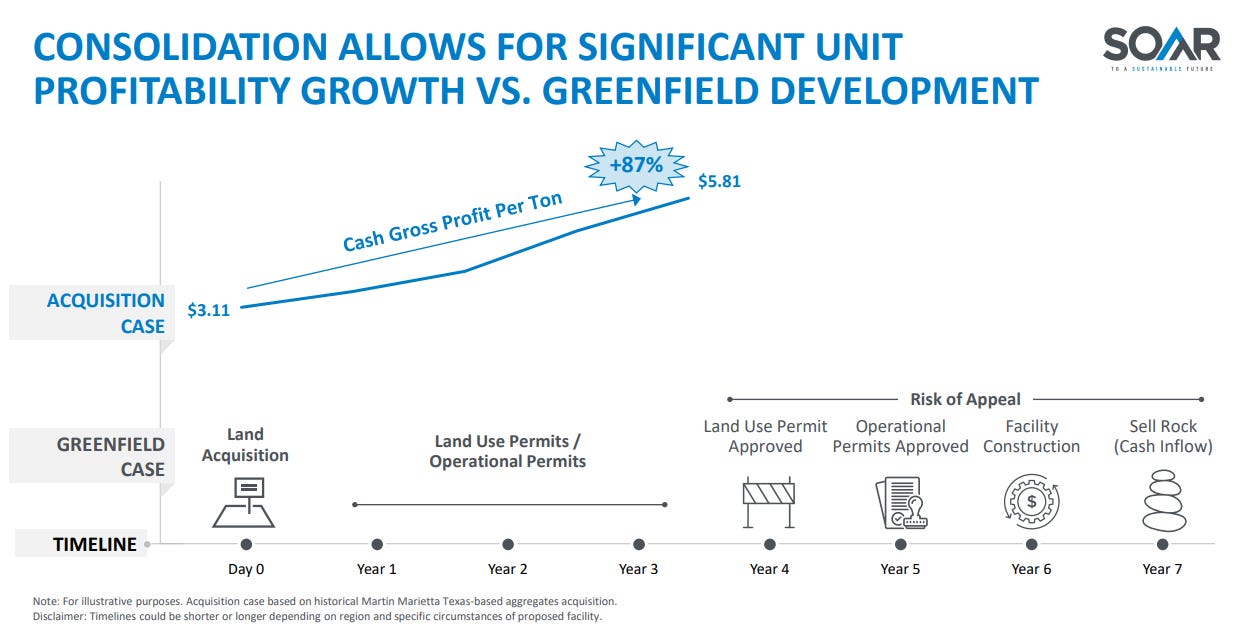

It’s not hard to see why primarily growing through acquisitions is the preferred method. Martin Marietta had an interesting graphic during the 2021 investor day outlining the economics of buying vs. greenfield-ing a new site.

Both from a timing and overall risk standpoint, growth through bolt-on acquisitions, as long as they aren’t de-worsification, are quite sensible in this industry.

While the incremental returns on capital are somewhat below what we typically look for, it’s still not bad considering how much capital can be redeployed at reasonable rates. They remind me a bit of well-run utilities who can deploy massive amounts of capital at respectable, but not unreasonably high, rates of return. The similarity isn’t surprising as utilities are the definition of (regulated) local monopolies.

All told over ethe last ten years the businesses have likely compounded per-share intrinsic value at a solid low/mid-teens rate, roughly matching the compounding of the stocks, as you’d expect over a long period of time.

I find the duration intriguing as well; in general I’ll favor a business that I think can earn low-teens returns with a very high degree of certainty for a decade or more compared to a business that might earn 25%+ for a few years but with a wide range of potential outcomes. Of course, I’d prefer both higher returns and lower uncertainty, and that usually means finding a business that is both cheap and high quality. Unfortunately when it comes to being cheap, the large aggregates businesses flunk.

Both stocks trade at persistently lofty valuations of around 30x-40x earnings, so there isn’t much shareholder yield to speak of, though that hasn’t hurt returns over the past decade. That said, there doesn’t appear to be much of a margin of safety at present prices. We look for stocks whose business return approximates Vulcan’s and Martin Marietta’s, but who also are likely to benefit from a (at least modest) valuation re-rating as icing on the cake. It’s tough to see that currently with these businesses, but things can change quickly.

A good description of these valuations might be expensive but not necessarily overpriced. A business that enjoys local monopolies, irreplaceable assets, supplies a product with no relevant substitute, has a long runway to soak up capital at good rates of return, and whose business model is likely to look similar 50 years from now should trade at a high valuation.

Things can change quickly in the market, though. Give us a real recession, or a meaningful short-term slowdown in the end markets these business supply, and the valuation could get appealing relatively quickly. During 2020 Martin Marietta traded for an average earnings multiple of less than 20x. In hindsight that was a pretty clear bargain, and I wouldn’t be surprised if we see it again in the years ahead.

This post is long enough but I may do a follow-up on another aggregates business that we’re looking at that is not as much of a pure play but also has an interesting special situation element and a valuation that’s less than half of VMC and MLM. More to come on rock pits, perhaps.

Do you have a “stranded” 401k from a past job that is neglected and unmanaged? These accounts are often an excellent fit for Eagle Point Capital’s long-term investment approach. Please contact us to learn more about opening a separately managed account with EPC.

Disclosure: The author, Eagle Point Capital, or their affiliates may own the securities discussed. This blog is for informational purposes only. Nothing should be construed as investment advice. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further details.

Did you ever write up that other rock pit?