7 Powers: A Summary of Competitive Advantages

In 2016 Hamilton Helmer published “7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy”. The book is the most comprehensive and simple summary of competitive “moats” that I’ve come across. Helmer is a long-time strategy consultant and investor who is credited with having an outsized influence on Reed Hastings’ early strategic pivot from DVD delivery to streaming at Netflix.

What follows is a summary of the seven business models that have proven to deliver lasting competitive advantages and some associated practical applications.

Power

Helmer defines Power as “a set of conditions creating the potential for persistent differential returns” and sets out to categorize the various business models that result in a company achieving Power. For investors, Power can be thought of as lasting competitive advantages resulting in a business achieving above-average results for substantial periods of time. Warren Buffett would refer to Power as a business’s “moat”. I’ll use those terms interchangeably.

Practically speaking, Power generally manifests itself in the form of persistently high returns on capital, durable above-market growth, and shareholder value creation via massive free cash flow generation over many years.

With that, let’s dive into the seven Powers.

Scale Economies

It’s no secret that scale economies are one of the most important competitive advantages that can accrue to large industry players. Munger has referred to benefits of scale as “ungodly” important. Helmer defines scale economies as:

A business in which per unit cost declines as production volume increases.

When a business crosses a certain volume threshold and fixed costs are spread over more and more units, the business either a) experiences significant margin expansion as operating expenses shrink as a percent of sales, b) passes savings along to consumers in the form of lower prices which in turn draws more customers into the business or c) some combination of these two.

Netflix has been a recent example of example scenario a) in that they were able to spread content cost over a vastly larger subscriber base than any streaming competitor. This allowed them to spend more on original content without hurting the business, and cemented them as one of the world’s leading content producers.

Costco is my favorite example of scenario b) as they use their bargaining power to extract rock-bottom prices from food distributors. Instead of keep those savings and enjoying margin expansion, Costco holds margins steady and passes the reduced prices along to customers thereby growing their customer base and creating value through membership volume growth instead of margin expansion.

Beyond leveraging fixed costs, there are a few other important advantages to scale, including:

· Volume/area relationships: These advantages occur when costs are tied to physical area of production. Bulk mixing tanks for scaled brewers would be an example here.

· Distribution network density: A great example of densification is garbage collection companies or FedEx/UPS delivery. It costs very little to add an incremental house to an existing route so each new customer in an area is very high-margin. A new garbage collection company would have a hard time matching the prices of an existing garbage collection provider as the new route would come with very little volume and costs per customer would be prohibitively high.

· Learning economies: The learning curve advantages that accrue to industry leaders are harder to quantify but no less important. Building airplane engines or manufacturing semiconductor chips are examples. It’s hard for challengers to quickly recreate decades of incremental manufacturing or pricing know-how.

· Purchasing Economies: Walmart procures more groceries than any chain in the country and therefore is able to negotiate lower prices than any competitor.

It’s important to understand the barriers to competitors that go hand in hand with each power. For scale economies, the barrier to competitors is an unwillingness for upstarts to accept high losses in order to gain market share.

Do not confuse scale economies with pure size, as scale advantages only create value if one firm has a sizeable relative scale position compared to competitors. If there are many scaled competitors of roughly the same size, some or all of the businesses may or may not enjoy benefits of scale that actually create value for shareholders.

The automotive OEMs and large airline companies are all massively scaled, but have by and large been terrible investments over the long term because none possess meaningful relative scale benefits compared to the others. Most benefits of scale flow right through to consumers, and the companies keep little benefit for themselves. The only airline to create meaningful shareholder value in the U.S. has been Southwest, and their advantage is thanks to Process Power (discussed later), not Scale Economies. As a general rule of thumb, industries with very high pre-production costs (like the airlines), slower growth, and/or little product differentiation often experience intense rivalry on price, mitigating many of the above scale benefits.

For this reason, I like to think of scale economies as a starting point with one or more of the following powers usually necessary for a truly formidable competitive position to exist and endure.

Network Economies

Network economies, also referred to as Network Effects, is a phenomenon whereby a product or service improves because of an increased amount of users. With Network Effects increased supply begets increased demand and so on. Helmer defines Network Economies as:

A business in which the value realized by a customer increases as the installed base increases.

Facebook is a classic example of network economies. Close to 3 billion people use Facebook’s properties (primarily Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp) each month. The size of Facebook’s network is a gravitational pull for more users as everyone wants to be on the same social platform as everyone else. In turn, as more users are attracted to the network it becomes an increasingly attractive and important place for businesses to direct digital marketing dollars because Facebook has the best chance of converting its massive user base into potential customers for advertisers. The data advantage from ~3 billion users is an insurmountable lead for advertisers other than Google, and is the reason that Facebook and Google have such a stranglehold on the lucrative digital advertising space.

More so than any of the other Powers, Network Economies trend toward winner-take-all or winner-take-most outcomes because of the insurmountable lead the first company enjoys once they are scaled. For example, there is virtually no reason for someone to switch from LinkedIn to an upstart professional social network. All prospective employers and other professionals already use LinkedIn and if I wanted to start an equivalent social network for professionals I would literally have to pay each user a non-trivial amount each year to switch to my sub-scale network.

Losses to unseat the dominant player become unpalatable very quickly for competitors, meaning once one firm achieves network economies in its target market, the game is basically over. For this reason network economies is one of the most durable Powers. It can be, however, bounded in various respects (geography, segmentation, etc.) and can be undone via poor execution - just ask eBay in the early 2000s.

Counter-Positioning

Counter-Positioning might be the hardest Power to spot as it unfolds, but is often looks obvious in retrospect. Helmer defines Counter-Positioning as:

A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business.

Counter-Positioning is how the David’s take on the Goliath’s of the business world. This happens when companies wedge themselves into a large incumbent’s market and the incumbent willingly decides to not compete because the incumbent believes it is not worth sacrificing their core business to match the newcomer’s offering.

Again I’ll point to Netflix as an easy example, but this time we’ll go further back in history. When Netflix launched its DVD by mail business it elected to not charge late fees. Blockbuster dominated the DVD rental industry and could have easily followed Netflix’s lead in eliminating late fees as well as offered DVD by mail. The problem was, late fees were a lucrative source of profits for Blockbuster. Further, Blockbuster emphasized an in-store experience and also reaped profits from selling concessions at check out. If Blockbuster would have emphasized a DVD by mail business it would have significantly negatively impacted its core business. So, it elected to do nothing.

Counter-Positioning is one of the most significant challenges for incumbent management teams because of how difficult it often is to accept short-term economic pain to compete against a new business model. The unwillingness to inflict “collateral damage” on a profitable existing business is often too much for a management team to accept, even if the standalone new business is attractive on its own.

It’s easy to understand – consider a 60 year old CEO who is two years away from retirement and has lucrative stock options vesting in the coming few years. Frequently that CEO will delay spending heavily and inflicting adverse economic outcomes on his base business just to ward off a seemingly small and irrelevant competitor. By the time the incumbent management team wakes up to the threat, it’s often too late. Counter-Positioning uses human biases to unseat previously dominant companies.

In hindsight, of course Blockbuster could and should have aggressively competed Netflix out of business, but because of the psychological bias of being unwilling to inflict pain on its business for long-term benefit (hard to blame them at the time!) Netflix drove Blockbuster to bankruptcy just years later.

Other great examples of counter positioning include Apple rapidly destroying Nokia’s position in the cell phone market and Vanguard challenging Fidelity in the asset management space via low-cost index funds.

For Counter-Positioning to succeed, two conditions need to be present:

1) The challenger’s offering needs to be attractive on a standalone basis. In other words, the product offering or value proposition needs to greatly exceed that of the incumbent.

2) The incumbent willingly accepts to not compete with the newcomer because of the collateral damage to its existing business, rather than a technological inability to compete.

Relative competitive position is important again here. A Counter-Positioning advantage applies only against the incumbent and consequently cannot be an exclusive source of Power. There can be several new firms utilizing Counter-Positioning against an incumbent, and parsing out who ultimately wins ex-ante among the newcomers can be difficult.

Switching Costs

High switching costs are one of my favorite Powers. Helmer’s definition of Switching Costs is:

The value loss expected by a customer that would be incurred from switching to an alternate supplier for additional purchases.

The reason I love businesses with high switching costs is because they benefit from high customer retention, making these businesses predictable and durable. Black Knight is a great example of a business with incredibly high switching costs. Black Knight is half of a duopoly and services roughly 50% of first-lien mortgages in the U.S. Banks utilize Black Knight’s software to generate mortgage documents, automate the origination business, manage massive regulatory requirements, service mortgages, and much more. Switching away from Black Knight’s software is akin to ripping the lungs out of a bank’s mortgage operation for very little benefit – something that simply isn’t worth the risk.

High switching costs can arise for financial, procedural or relational reasons. For example, installing a new ERP system is incredibly costly, resulting in companies sticking with sub-optimal solutions rather than spending the time and money to switch vendors. On the procedural front, all engineers for the past few decades have been trained on a few CAD systems, like AutoCAD. Because these skillsets are transferred from one generation of engineers to the next, Autodesk’s products have incredible inertia which results in high switching costs to competing design software. Consumers sticking with a bank even though they feel nick-and-dimed to avoid the hassle of moving checking accounts is another good example. Relational switching costs develop when customers and service providers become emotionally connected. This can be common in the service industry such as accounting or consulting.

The resulting customer stability affords companies that enjoy high switching costs the option to a) charge higher prices than others for equivalent products and more importantly, b) cross sell additional products and services to a captive customer base. Frequently, add-on acquisitions can be accretive for these businesses as well given the large installed base to which new products can quickly be offered.

While high switching costs are great, they only apply to a business’s current customer base and acquiring new customers in a mature market is usually difficult. For this reason, if you can identify a business with high switching costs that is also early in its growth trajectory you may really be onto something interesting.

Even though volume growth will slow as an industry matures, companies with this Power often exhibit strong operating leverage and will see margins expand faster than revenue for long periods of time, making even modest topline growth valuable for shareholders.

Branding

Branding is one of the easier Powers to understand because we experience it as consumers all the time. Branding Power is defined as:

The durable attribution of higher value to an objectively identical offering that arises from historical information about the seller.

Put simply, if a business can charge higher prices compared to others that offer essentially the same product or service, it’s likely that they are harnessing brand power. The associated outsized returns can last for decades given a strong enough brand.

The strongest barrier from competition for strong brands is time. It usually takes decades, or even longer, to amass enough brand power that no amount of money from a competitor is likely to unseat. For example – if you gave me $100B to recreate Coca-Cola’s brand or Tiffany’s jewelry brand, I just couldn’t do it. Coke and Tiffany’s have been building their reputations since the 1800’s, and the feelings associated with those companies cannot be recreated even if I could formulate an equivalently tasting cola or source the same quality of diamonds.

Strong brands are insulated thanks to economic hysteresis. Those hoping to challenge a strong brand must be ready to invest very large and unknown amounts of capital for years with an uncertain payoff. Further, brands often enjoy substantial trademarks and IP providing another buffer against competition.

Of course, no brand is completely bulletproof. The biggest things to watch out for are brand dilution and changing consumer preferences. Helmer references upscale retailers like Halston that went “downstream” and began designing clothes for JC Penny in search of new customers. This ended up eroding their premium brand permanently. Perhaps Peloton is headed down a similar path by discounting their premium product to try and capture a new segment of lower income customers. Some brands capture the hearts and minds of one generation but not the next as consumers preferences slowly change. Additionally, some brands travel internationally while others have a much narrower geographic reach. Snickers is one of the only candy bars that enjoys worldwide brand power. The reason why? Your guess is as good as mine.

Cornered Resources

I think of the Cornered Resource Power as similar to a company that possesses “irreplaceable assets”. Helmer explains this Power as:

Preferential access at attractive terms to a coveted asset that can independently enhance value.

Cornered Resources can take the form of physical, intangible, or even human. Texas Pacific Land Corp’s (TPL) vast ownership of land in Texas and resulting royalty stream on resources extracted from the land is an example of a physical cornered resource. Copart’s land ownership and EPD’s pipelines are other examples. Patents on blockbuster drugs or other forms of regulatory capture are other strong forms of this Power. Tobacco companies enjoy exclusive access to tobacco distribution that are impossible to recreate today, representing a daunting distribution moat. Helmer argues that the early brain trust of John Lasseter, Ed Catmull, and Steve Jobs at Pixar was an example of a Cornered Resource responsible for tremendous value creation for Pixar.

To qualify as a Cornered Resource, an asset must be:

· Idiosyncratic – it must be an identifiable unique asset not available to others;

· Non-arbitraged – if a company gains access to a resource but pays a price so high that it arbitrages out the benefits, then it hasn’t gained any value;

· Transferable – a resource that creates value at one company but not another is not a Cornered Resource, as something else must be driving the value behind the asset;

· Ongoing – benefits from the resource must be lasting;

· Sufficient – the resource in question must by itself (assuming adequate execution) be responsible for outsized economic results.

Process Power

Unlike a typical Cornered Resources, Process Power is often qualitative. Process Power is defined as:

Embedded company organization and activity sets which enable lower costs and/or superior product, and which can be matched only by an extended commitment.

Much like Branding, Process Power can only be built over decades and becomes engrained in company’s culture allowing for superior cost structures, product offerings, and economics. Businesses that develop Process Power have a “secret sauce” that’s often more tacit than explicit.

Toyota is Helmer’s preferred example with its “Toyota Production System” (TPS) developed over decades. The TPS methodology has resulted in consistently higher quality improvements and cost reductions compared to all automotive competitors. Constellation Software appears to have assembled significant Process Power with its VMS acquisition machine deeply embedded within its business. GEICO and Progressive have harnessed this dynamic in P/C insurance.

The difference between Process Power and simple operational excellence is that Process Power only emerges after agonizing bottoms-up trial and error over long periods of time, and is therefore very difficult for others to copy and can result in a lasting competitive advantage. TPS is widely studied and all auto OEMs attempt to replicate its benefits, but it’s become evident that a company can no more recreate Toyota’s internal systems by reading about them than I could become a professional golfer by watching the PGA tour.

Summary

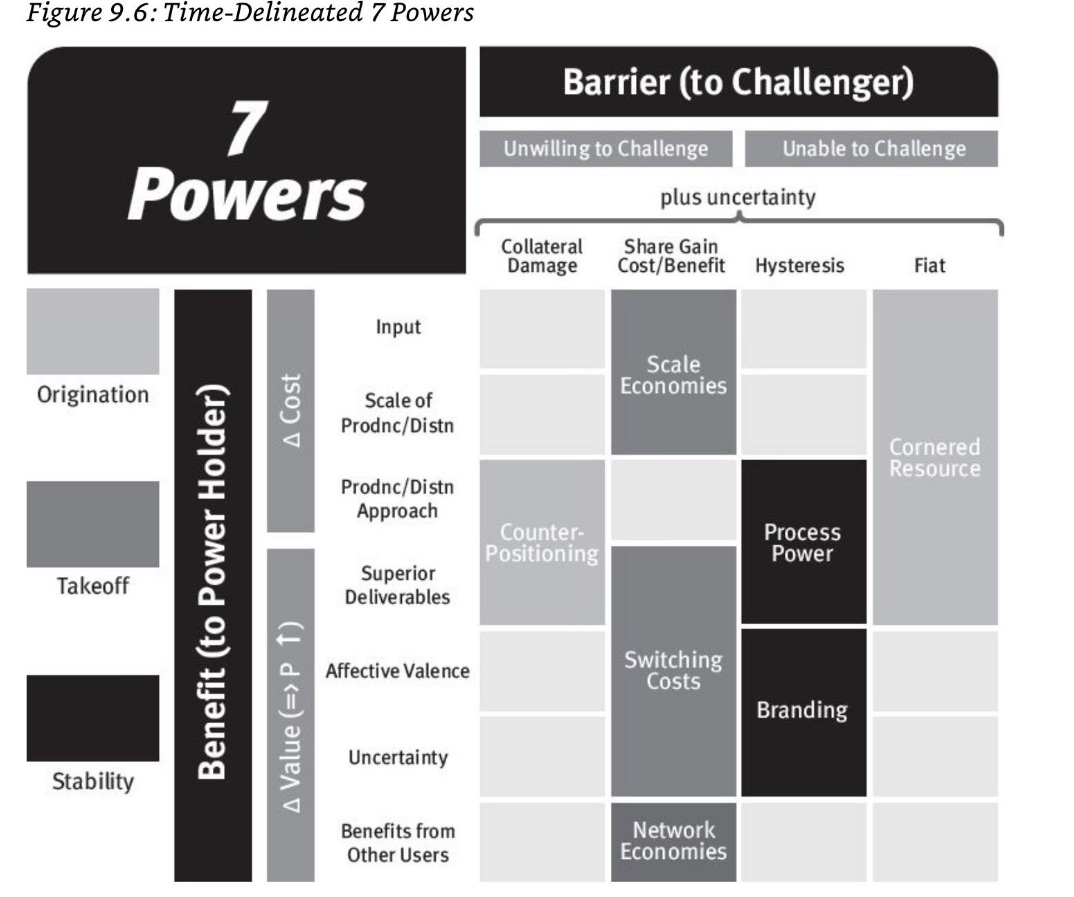

A few Helmer graphics summarize the book very well.

This first chart displays each Power as well as the benefit to the company and the barrier to potential competitors. For instance – businesses benefitting from switching costs enjoy affective valence from customers (good feelings or comfort around the product/service) and are protected by prohibitively high cost to gain share from competitors (e.g. a competitor would have to pay a customer a significant amount to undergo the risk and pain of switching services).

Here’s a less busy summary of each Power. Perhaps I could have posted these two graphics and called it a day!

I’ve only scratched the surface of Helmer’s discussion around Power, and I’d highly recommend the book to anyone that works in or leads a business. In the second half of the book Helmer discusses at what point in the business life cycle Power emerges, and how different paths to Power can be forged. It can be a little academic at times (Helmer is an econ PhD from Yale after all) but overall it’s very digestible. It’s hard to imagine any business leader not being better off by working to develop one or more of these Powers for their company.

Practical Application

I find Helmer’s framework a useful tool when asking the question “why”. Why does a company consistently earn superior returns on capital? Why might a company enjoy superior growth rates for many years? How long might these superior returns last? Identifying potential sources of Power among businesses and stocks you are studying is a useful exercise and helps build comfort with different competitive positions (or lack thereof).

No one always gets it right, but just attempting to understand if a business has an enduring competitive moat is half the battle. If an investor’s aim is to buy good businesses it’s tough to think of a better checklist than Helmer’s 7 Powers as a starting point. Studying businesses that meet some of the above criteria amounts to fishing in a stocked pond. This isn’t the way to invest successfully but it certainly is a way.

Understanding a company’s Power is also very helpful when enduring the inevitable sell-offs that long-term investors experience in individual stocks. This is great timing for Facebook shareholder’s after the stock’s seemingly biannual selloff this week. Answering the question of – “did the stock sell off because the company’s Power was permanently impaired?” – can be a great starting point in trying to understand if price fluctuations are driven by fundamentals or emotion. The goal is to take advantage of the latter.

The final piece for investors is assessing what price to pay for companies that possess Power, but that’s for another day.

If you would like to invest with Eagle Point Capital or connect with us, please email info@eaglepointcap.com. Thank you for reading!

Disclosure: The author, Eagle Point Capital, or their affiliates may own the securities discussed. This blog is for informational purposes only. Nothing should be construed as investment advice. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further details.