Buffett and Buybacks: Six Case Studies

General Dynamics, IBM, Apple, Occidental, HP, and Bank of America

I've been studying Buffet for years and have noticed a few simple but profound patterns in the way he invests. He seems to looks for:

A 9-10x pre-tax earnings multiple (or less);

Replication Mode — Simple, predictable, profitable businesses drowning in cash; and

High Shareholder Yield — "Drowning in cash" isn’t enough. Buffett wants the cash returned to shareholders via dividends and buybacks. He often buys when there's a change in capital allocation or management clarifies their capital allocation policy.

Today I will present a few case studies showcasing Buffett’s preference for a high shareholder yield and show how he uses a change in capital allocation to time his purchases. I’ll cover General Dynamics, IBM, Apple, Occidental Petroleum, HP, and Bank of America.

General Dynamics

In the six months after the Berlin Wall fell defense stocks cratered 40%. General Dynamics looked to be in such a poor position that one defense analyst called it the "lowest of the low."

In January 1991 Bill Anders took over as CEO. His unusual background — he was the astronaut who took the iconic Moonrise photograph — foreshowed his unusual tactics.

Anders based his strategy on one key insight: the defense industry had significant excess capacity after the Cold War. Companies would either need aggressively shrink by selling businesses or grow through acquisition of those businesses.

Anders decided to sell every business that wasn’t number one or two in its market. Anders simultaneously tightened operations and reduced working capital. He promoted decentralized decision making and reduced headquarters staff.

These efforts produced a tsunami of cash. General Dynamics generated $5 billion of free cash flow in less than three years after losing $600 million in 1990.

Most CEOs would have redeployed that capital into R&D or acquisitions. Anders used tax-efficient techniques to return it to shareholders. This is the shrink-to-grow strategy I wrote about here.

In The Outsiders (Dan wrote about that book here) William Thorndike wrote:

It is very, very rare to see a public company systematically shrink itself; as Anders summarized it to me, “Most CEOs grade themselves on size and growth… very few really focus on shareholder returns.”

It is similarly rare (outside of the CEOs in this book) to see a company systematically return proceeds to shareholders in the form of special dividends or share repurchases. The combination of the two was virtually unheard of, particularly in the tradition-bound defense industry.

Anders declared three special dividends that amounted to over 50% of General Dynamic’s equity. Since Anders had divested such a large portion of General Dynamics these dividends were deemed a tax free return of capital. Anders followed up with a $1 billion tender offer to repurchase 30% of General Dynamic’s stock.

Anders’ unusual capital allocation caught Buffett’s eye. In Berkshire’s 1992 annual report Buffett wrote:

We were lucky in our General Dynamics purchase. I had paid little attention to the company until last summer, when it announced it would repurchase about 30% of its shares by way of a Dutch tender. Seeing an arbitrage opportunity, I began buying the stock for Berkshire, expecting to tender our holdings for a small profit. We've made the same sort of commitment perhaps a half- dozen times in the last few years, reaping decent rates of return for the short periods our money has been tied up.

But then I began studying the company and the accomplishments of Bill Anders in the brief time he'd been CEO. And what I saw made my eyes pop: Bill had a clearly articulated and rational strategy; he had been focused and imbued with a sense of urgency in carrying it out; and the results were truly remarkable.

In short order, I dumped my arbitrage thoughts and decided that Berkshire should become a long-term investor with Bill. We were helped in gaining a large position by the fact that a tender greatly swells the volume of trading in a stock. In a one-month period, we were able to purchase 14% of the General Dynamics shares that remained outstanding after the tender was completed.

Buffett made a killing but sold when Anders retired. He should have held on. A dollar invested when Anders took over became $30 seventeen years later.

IBM

Buffett bought IBM in 2011 and sold it in 2017. He earned a ~5% annual return on the investment (including dividends), which underperformed the S&P 500 and Berkshire. Nonetheless, IBM showcases several of the qualities Buffett looks for in an investment.

Speaking live on CNBC in November 2011, Buffett explained that he’d been reading IBM’s annual report for fifty years. The 2010 report hit him “between the eyes.” It made him realized that IBM enjoyed advantages in finding and retaining clients.

It's a company that helps IT departments do their job better. It is a big deal for a big company to change auditors, change law firms. There is a lot of continuity to it.

IBM’s capital allocation also caught Buffett’s eye.

The other thing I would say about IBM, too, is that a few years back, they had 240 million options outstanding. Now they probably are down to about 30 million. They treat their stock with reverence which I find is unusual among big companies. They really are thinking about the shareholder.

Buffett praised IBM’s capital allocation and buybacks in Berkshire’s 2011 letter.

But their financial management was equally brilliant, particularly in recent years as the company’s financial flexibility improved. Indeed, I can think of no major company that has had better financial management, a skill that has materially increased the gains enjoyed by IBM shareholders. The company has used debt wisely, made value-adding acquisitions almost exclusively for cash, and aggressively repurchased its own stock…

In the end, the success of our IBM investment will be determined primarily by its future earnings. But an important secondary factor will be how many shares the company purchases with the substantial sums it is likely to devote to this activity. And if repurchases ever reduce the IBM shares outstanding to 63.9 million, I will abandon my famed frugality and give Berkshire employees a paid holiday.

IBM’s 2010 annual report showed record revenues and earnings and explained how the company allocates capital.

Over the past decade, we have returned $107 billion to you in the form of dividends and share repurchases, while investing $70 billion in capital expenditures and acquisitions, and almost $60 billion in R&D.

IBM’s capital return was particularly aggressive in 2010. It spent $18.4 billion on buybacks and dividends which was 11.4% of its average market cap.

On CNBC Buffett elaborated that he didn’t buy IBM just because they said they’d repurchase shares. He waited until they actually did it. Trust, but verify.

I wasn't smart enough to do it [buy IBM] when Lou first came in. In other words, everybody says they're going to do it [buyback stock]. I was smart enough, if you want to call that, we'll find out whether it's smart or not, but to recognize that after it's been done, and then way too late. I was—it was the same way with the railroads. I mean, something I should have spotted years earlier, you know, finally be—just hit me between the eyes and it was there.

In other words, Buffett judged that IBM was in replication mode. Its high switching costs made sales sticky and earnings predictable. Buybacks ensured shareholders would actually benefit from the company’s earnings.

Although IBM is a good case study of what Buffett looks for in a stock, Buffett’s judgement proved flawed. IBM’s advantages weren’t as strong as expected and the company struggled to increase sales.

In 2017 Buffett sold IBM for a loss (before dividends) and told CNBC:

I was wrong… IBM is a big strong company, but they’ve got big strong competitors too. I don’t value IBM the same way that I did six years ago when I started buying... I’ve revalued it somewhat downward.

IBM proves that geniuses like Buffet are occasionally wrong. If he can be wrong, we can too. A heavy does of humility and a wide margin of safety are mandatory.

It’s worth noting, however, that although Buffett was wrong about IBM he still didn’t lose money. Buffett paid ten times pre-tax earnings for IBM, which provided him a wide margin of safety. If you can avoid losing money even when you are wrong, you’re doing something right. That’s what Munger means when he says, “Avoiding stupidity is easier than seeking brilliance.”

Apple

Apple is one of Buffett’s greatest investments of all time. The stock has appreciated four fold since he began buying, a 26% CAGR. The investment has swollen to $122 billion — 40% of Berkshire’s domestic stock portfolio.

Apple’s buyback saga goes back a ways. In 2013 David Einhorn sued the company to try to get it to return its $137 billion cash hoard to shareholders. Apple had laid out a $45 billion capital return program in 2012 that Einhorn that was too meek.

A year later, Carl Icahn wrote an open letter to Tim Cook asking for more buybacks. Icahn noted that Apple traded for just eight times earnings, half of the S&P 500’s multiple, but was expected to grow 30% per year.

Apple increased its capital return program each year. By the end of 2014 its cumulative buyback authorization was $130 billion. Nevertheless, Apple’s net cash balance continued to grow. Free cash flow was growing faster than its buybacks.

In April 2015 Apple reported record earnings and once again increased its buyback authorization. This time it wasn’t shy. It increased the buyback authorization by 50% to $200 billion.

Apple’s cash position peaked in 2016, the same year Berkshire started buying. The first billion or so Berkshire spent on Apple was probably Ted Weschler’s doing.

Around the same time Berkshire director and octogenarian Sandy Gottesman told Weschler, "I felt like I lost a piece of my soul" after his iPhone slipped out of his pocket and was left in a taxi.

Weschler shared the anecdote with Buffett who was surprised that one of his peers could be so enamored with technology. Buffett began to read Apple’s annual reports but his ah-ha moment came at a Dairy Queen.

During a weekly trip to Dairy Queen with his grandchildren, Buffett noticed that no one could take their eyes off their smartphones. In After Steve Tripp Mickle wrote, “He realized that Weschler was right: the iPhone wasn't tech, it was a modern-day Kraft Macaroni & Cheese.”

Buffett began buying Apple in 2016 Q4, around the time Apple’s cash positioned peaked. Buffett paid 12.6x earnings (10x pre-tax) for Apple, which was earning 36% on its equity. The stock paid a 2% dividend and buybacks were adding another 5% of yield, bringing the total to 7%.

In Berkshire’s 2020 letter Buffett wrote:

Berkshire’s investment in Apple vividly illustrates the power of repurchases. We began buying Apple stock late in 2016 and by early July 2018, owned slightly more than one billion Apple shares (split-adjusted). Saying that, I’m referencing the investment held in Berkshire’s general account and am excluding a very small and separately-managed holding of Apple shares that was subsequently sold. When we finished our purchases in mid-2018, Berkshire’s general account owned 5.2% of Apple.

Our cost for that stake was $36 billion. Since then, we have both enjoyed regular dividends, averaging about $775 million annually, and have also – in 2020 – pocketed an additional $11 billion by selling a small portion of our position.

Despite that sale – voila! – Berkshire now owns 5.4% of Apple. That increase was costless to us, coming about because Apple has continuously repurchased its shares, thereby substantially shrinking the number it now has outstanding.

[..]

The math of repurchases grinds away slowly, but can be powerful over time. The process offers a simple way for investors to own an ever-expanding portion of exceptional businesses.

And as a sultry Mae West assured us: “Too much of a good thing can be... wonderful.”

Occidental Petroleum

Buffett’s latest buy is Occidental Petroleum. Buffett first got involved in April 2019 when Berkshire helped finance the company’s hostile takeover of Anadarko Petroleum. Berkshire gave Oxy $10 billion of cash for $10 billion of preferred shares (yielding 8% or $800 million) and warrants to buy 83.9 million common shares of Occidental at $59.62.

Occidental planned to divest $10-15 billion in assets and achieve $3.5 billion in savings from the tie-up. Oxy also thought it could improve the yields of Anadarko’s wells in the Permian Basin.

Buffett told CNBC how it went down:

It happened right here. Last Friday, less than a week ago, I got a call in the middle of the afternoon from Brian Moynihan, the CEO of Bank of America. And he said that they were involved in financing the Occidental deal, and that the Occidental people would like to talk to me.

Buffett arranged a meeting with Occidental CEO Vicki Hollub for Sunday morning.

They arrived at 10 a.m. And by 11 we had a deal. And they had us committed unequivocally, come hell or high water, for $10 billion.

Buffett explained why he got involved:

Oil prices are the big determiner over time... same thing is true if you are in copper. Oil prices are enormously important.

I was familiar with Occidental and definitely familiar with the Permian Basin, although I’ve never been there. If I were there, I wouldn’t know what to do. It was a sensible deal for us.

It was sensible deal for them. I proposed it, and they decided whether it made sense and then when we finished at 11, they went back to the plane. I called [our attorney] Ron Olson, he’s on the West Coast so it was 9 a.m. his time, and I said we need to get this done by tomorrow evening.

Crude oil was $57 then but plunged below zero in April 2020. That prompted Oxy to pay Berkshire its Q2 preferred dividend in common shares rather than cash. Berkshire immediately sold them for $9-25 per share (the stock’s Q2 range).

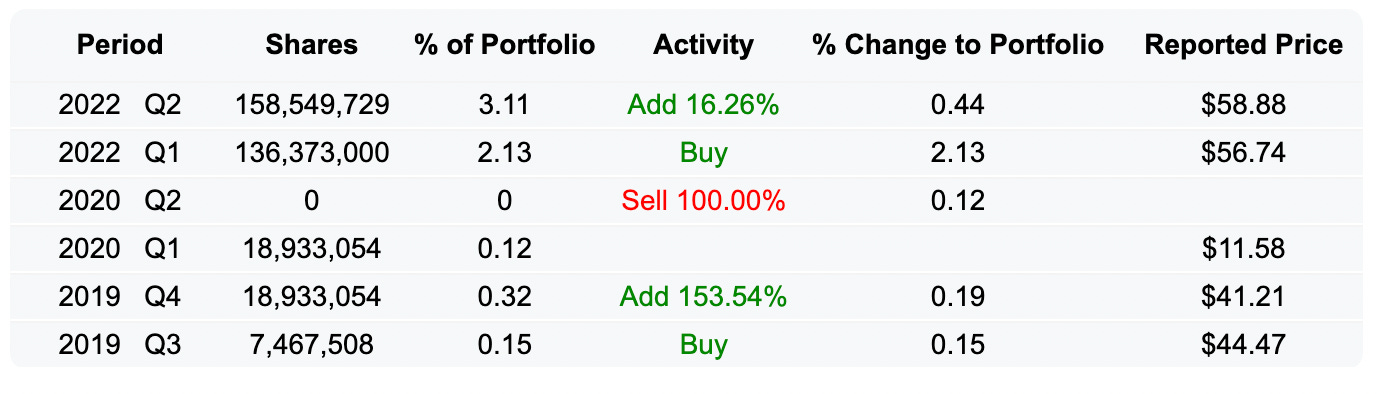

Buffett then sat on his hands for the better part of two years before buying billions of dollars of Oxy common shares in Q1 2022 for $57 per share.

Why did Buffett sell in Q2 ‘20 at $9-25 but buy in Q1 ‘22 at $57? Buffett explained at Berkshire’s May 2022 shareholder meeting.

And in the case of Occidental specifically, they’d had an analyst presentation of some — I don’t know whether it was a quarterly one or what it was exactly — but I read it over a weekend — and that was the weekend when the annual report came out — I read it over a weekend.

And what [CEO] Vicki Hollub was saying made nothing but sense. And I decided that it was a good place to put Berkshire’s money.

And then I found out in the ensuing two weeks — it was there in black and white — there was nothing mysterious about it — but Vicki was saying what the company had gone through and where it was now and what they planned to do with the money.

Buffett reiterated this on CNBC.

I read every word, and said this is exactly what I would be doing. She’s running the company the right way. We started buying on Monday and we bought all we could.

Aside — note how much of Buffett’s reading and deal-making happens on the weekend. If you don’t love investing so much that you’re working (some) weekends, you’re going to struggle to compete against those that are excited to.

Reading Oxy’s Q1 call was a eureka moment for Buffett, much like reading IBM’s 2010 annual report. He liked that Oxy clearly laid out where they’ve been and where they’re going, just like IBM.

Oxy’s Q1 call explained that it had repaid enough debt that it could begin returning a significant portion of its profits to shareholders.

We now expect that our net debt will be below $25 billion by the end of the first quarter of 2022, which will mark a change in how excess cash flow will be allocated going forward.

Like General Dynamics, Oxy’s capital return program seems like the main reason Buffett bought. Importantly, Oxy was also cheap — Buffett paid $57 per share in Q1 ‘22, 10x Oxy’s annualized Q1 earnings.

HP

Buffett also bought a sizable slug of HP in Q1 ‘22. I don’t know much about the stock or why Buffett bought it, but a quick glance at the company’s Value Line report shows a lot to like. The stock trades for 8x PE, earns 63% on its capital, and has been buying back shares at a blistering rate — 10.6% in 2020 and 16.3% in 2021.

Bank of America

Like Occidental, Buffett’s Bank of America (BAC) investment started with an investment in preferred shares.

In 2011 Berkshire bought $5 billion of preferred shares from BAC, along with warrants to for 700 million common shares. According to CNBC’s Becky Quick:

Buffet just dreamt this idea up on Wednesday morning while he was the bathtub. He had never spoken with Brian Moynihan before. In fact, he didn't even have his phone number. But as the press release points out, this is something an outreach that Buffett made to Brian Moynihan of Bank of America.

He had one of his assistants call Moynihan's assistant and offered his private number up. I guess they spoke at some point mid-morning yesterday and Moynihan was receptive to this whole idea.

What's amazing is this went from being thought up yesterday morning to actually being initiated just 24 hours later. Now Buffett says he thinks it's a good $5 billion investment. I asked him why now and he said he thinks it's better than anything else that I can think of at the time.

In June 2017 Bank of America passed the Fed’s stress test and more than doubled its buyback authorization. BAC had been spending $4-5 billion per year on buybacks but said they’d now repurchase $12 billion over the next twelve months. BAC also raised its dividend. Buffett began buying a few days later. Bank of America was trading for just 10x earning.

BAC is most similar to Oxy, where buying preferreds led to buying common shares once the company paid down enough debt to begin buybacks. Note that Buffett doesn’t try to anticipate changes in capital allocation, he simply waits for them to occur. That’s avoiding stupidity rather than seeking brilliance.

Closing Thoughts

There seem to be three key ingredients to many of Buffett’s investments:

A 9-10x pre-tax earnings multiple (or less);

Replication Mode — Simple, predictable, profitable businesses drowning in cash; and

High Shareholder Yield — Large buybacks on top of dividends.

These are just my observations. They’re not hard and fast rules. There is definitely confirmation bias in my examples. Buffett has absolutely invested when there were no shareholder yield present.

At EPC we think of a stock’s forward returns as the sum of its yield, growth, and change in P/E multiple and I think Buffett does too.

Growth and changes in P/E multiple get all of the attention, but yield is the most stable. It seems like 90%+ of VIC theses hinge on forecasts of high growth or multiple expansion. While growth and multiple expansion may be sexy, they’re difficult to predict. Yield is more predictable, especially if you wait for payouts to be announced (vs buying in anticipation).

If you would like to invest with Eagle Point Capital or connect with us, please email info@eaglepointcap.com. Thank you for reading!

Disclosure: The author, Eagle Point Capital, or their affiliates may own the securities discussed. This blog is for informational purposes only. Nothing should be construed as investment advice. Please read our Terms and Conditions for further details.

This was great. Excellent work

nice breakdown, many thanks Matt. Thinking as outsiders is indeed a constantly underestimated quality of CEOs which Buffett obviously paid enough attention to.

Btw, the book shall be "After Steve" :)